Prescription death: Oregon struggles to implement new law

Implementing a dangerously flawed and loosely written new law is not easy to do. That is the reality currently facing Oregonians as they attempt to iron out the ambiguities, plug up the loopholes, and otherwise deal with the hollow assurances given by physician-assisted suicide (PAS) supporters to get voters to approve the Oregon Death with Dignity Act (DWDA), also known as Measure 16. This new law, the only one of its kind in the world, allows doctors to intentionally prescribe lethal medications to end the lives of patients believed to be terminally ill.

Originally passed in 1994 by the narrowest of margins, but subsequently barred from taking effect by court injunction, the PAS measure was again before the voters for reconsideration in a special November 1997 election. While every attempt was made during the campaign to inform voters about the DWDA’s “fatal flaws,” a majority of those voting chose to ignore the warnings and instead defeated the measure which would have repealed the law. (See Updates, 11-12/97:1; 8-10/97:1.)

Professional PAS guidelines issued

The fact that the DWDA has serious problems was confirmed when a 25-member task force, representing a wide range of Oregon’s health care providers and organizations, recently issued its 91-page manual recommending practice guidelines for implementing the new PAS law. This first-of-its-kind guidebook, which was two years in the making, is the product of the Task Force to Improve the Care of Terminally-Ill Oregonians, convened by the Center for Ethics in Health Care at the Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. The guidelines are recommendations only and not binding on health care providers or patients.

Under the heading “Purpose of the Guidebook,” the Task Force claims that it has “endeavored to maintain a neutral position” on the issue, but designed the guidebook “to be a comprehensive reference book on all aspects of putting the Act into practice.” “Our intent in developing the guidebook,” according to the Task Force, “has been to carefully think through scenarios in detail and to recommend actions that will optimize care and minimize harm….” [Task Force to Improve the Care of Terminally-Ill Oregonians, The Oregon Death with Dignity Act: A Guidebook for Health Care Providers, pp. 3-4; hereafter cited as Guidebook.]

The guidebook’s emphasis is clearly on minimizing harm, harm which would likely be a consequence of the DWDA. Many of the cautions and warnings raised in the guidebook are the same ones raised by PAS opponents during the campaign to repeal the law last November, warnings PAS supporters labeled scare tactics and lies.

One such warning deals with the public’s perception that death under the new law would be quick and easy. The Task Force explicitly recommends that the attending physician should advise “the patient and family that death will not be immediate and may take hours.” [Guidebook, p. 18] In the chapter on “Pharmacy Information,” the Task Force echoes the repeal campaign’s assertions that oral medications could cause lingering deaths, vomiting and other complications, and might not even be fatal:

“Possible causes of delayed death may include vomiting, malabsorption or other factors. The amount of medication ingested may have been sufficient to produce death, but if a portion of the total dose was not absorbed for any reason, the expected outcome may not be realized…. Predicting an effective lethal dose and the speed with which it will cause death for an individual with any degree of certainty is difficult…. The attending physician should also tell the patient…that the medication may not end life as expected; and that complications are possible.” [Guidebook, pp. 33-34; emphasis added]

The guidebook reveals other significant problem areas and gaps contained in the new law as well. For example, while the DWDA expressly prohibits doctor-administered lethal injections, the law is unclear as to whether or not an attending physician can prescribe an “injectable drug” for a patient so that the patient could self-administer the lethal injection. [Guidebook, p. 33.] Moreover, the DWDA contains no guidance for relaying a patient’s death wish and plans between the attending physician and other health care providers, such as emergency room physicians and emergency technicians (EMTs). [Guidebook, p.38] As the Task Force points out, “Confidentiality is of paramount importance in ensuring compliance with this Act.” And, while the DWDA requires the Oregon Health Division to maintain reporting data regarding the practice of PAS and to review a “sample” of records annually, the law does not give the Health Division any enforcement authority and “is silent on what the Division should do when non-compliance is encountered.” [Guidebook, p. 44]

A question of degree… and much more

Another huge question regarding the proper implementation of the PAS law is: To what degree can a care-giver provide assistance to a patient at the time that death is induced? By design, the DWDA only covers actions taken up until the time that the physician writes the lethal prescription. It does not cover actions taken at the time of the patient’s induced death, which could occur at a much later date. While the DWDA appears to leave intact the state’s prohibition against a “lethal injection” or any direct action by another person to end the patient’s life (“mercy killing or active euthanasia”) [DWDA, 127.880 §3.14], it does not specifically state anywhere that the patient must self-administer the deadly medication. During the campaigns to win voter approval, the idea that a patient would be required to self-administer prescribed pills was assumed to be what the new law stipulated.

In its guidebook, the Oregon Task Force also assumes patient self-administration but does point out that the new law is unclear on precisely what form of assistance can be given at the time the lethal medication is administered. According to the Task Force, “The Death With Dignity Act does not provide guidance on the degree of assistance with self-administration, if any, which may be given by another person.” [Guidebook, p. 28] The law only stipulates that no one who is present for the induced death of a qualified patient will be subject to civil/criminal liability or professional disciplinary action. [DWDA, 127.885 §4.01(1)]

Members of the Oregon Nurses Association (ONA) have expressed concern that, without further clarification on the assistance issue, nurses might be open to disciplinary action. The State Board of Nursing has announced plans to formulate standards for nurses to follow. [UPI, 3/8/98] “Assistance with medications is a very big gray area, and that has led many nurses to believe that ultimately… we’re going to be confronted with some kind of required assistance, whether it’s opening the bottle, opening the package…,” explained Susan King, ONA administrator for professional services. “We need to know where we stand.”

An informal legal opinion on this question was given by Deputy State Attorney General David Schuman to the joint House and Senate judiciary committees dealing with “fine-tuning” the DWDA. “Although the answer to this question is not without some doubt,” Schuman said, “a physician or nurse may probably administer oral medications and assist in self-administration under Measure 16 [DWDA].” In a subsequent interview, Schuman elaborated, “I think the theory is that if normal medical practice allows nurses to aid in the administration of medications, there’s nothing in Measure 16 that would change that.” “Administer,” according to Schuman, could mean spoonfeeding the deadly drug. He said that he based his opinion on state nursing practice statutes governing how nurses administer medication.

Some legislators were shocked by Schuman’s opinion. “I think that’s directly contrary to the direct language of the [assisted suicide] statute and the spirit of the statute,” said Sen Ken Baker (R-Clackamas), joint committee co-chair. “When you involve another person, then you start to lose your self-determination, and hat’s the key behind the entire statute,” he added. But Barbara Coombs Lee, DWDA co-author and executive director of the Compassion in Dying Federation, disagrees. She told The Oregonian that assistance such as spoonfeeding would not compromise the spirit of the PAS statute. “In one sense, only the patient can administer an oral medication because only one person can eat it,” she said. [The Oregonian, 3/4/98]

The idea that the lethal prescription must be for oral medication only is another assumption made by most Oregonians. However, nowhere in the DWDA does it stipulate that the deadly drug must be in pill or oral form. If Schuman is correct—that nothing in the new law changes the “normal medical practice” of how nurses and doctors administer medications to patients—then the use of an intravenous (IV) line to administer lethal medication to a qualified patient who, for example, cannot swallow, would appear to be allowed under the DWDA. In the Netherlands, where assisted suicide and euthanasia have been part of medical practice for over 20 years, IV lines are commonly used to administer lethal medications. The Dutch even use lethal rectal suppositories at times to end patients’ lives. [G.K. Kimsma, “Euthanasia and Euthanizing Drugs in The Netherlands,” in M. Battin and A. Lipman, eds., Drug Use in Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia, 1996, p. 199]

Learning from the Dutch

It is because of the Dutch experience with assisted suicide and euthanasia that a self-appointed delegation of Oregon health professionals has announced plans to visit the Netherlands on a fact-finding mission. “We want to see what we have in common and where we have differences,” explained Joseph Schnabel, a Salem Hospital pharmacist and Oregon Board of Pharmacy member. Other members of the delegation include right-to-die activist Dr. Peter Rasmussen; Dr. Bonnie Reagan, chairman of the Task Force subcommittee which produced the DWDA guidebook; and Kathleen Haley, executive director of the Oregon Board of Medical Examiners.

The delegation’s itinerary has been planned by Dutch anesthesiologist Dr. Pieter Admiraal, often called the father of Dutch euthanasia. Admiraal, who has taken part in well over 100 euthanasia deaths, has been very critical of the Oregon law, warning that deaths under the DWDA may be lingering and difficult for family and friends to witness. According to Admiraal, the doctor should be present to give the patient a lethal injection if death does not occur within 5 hours — an action prohibited by the DWDA. (See Update, 8-10/97:1.) Admiraal has arranged for the Oregon delegation to meet with the Dutch Justice Ministry, the Royal Society of Pharmacy, the Royal Society of Medicine, medical faculty of Amsterdam’s Vrije University, and the Dutch Society for Voluntary Euthanasia. Reportedly, the hope is that the delegation will gather needed information to develop more PAS practice guidelines to help doctors, pharmacists, nurses, state officials, and others to interact appropriately. [AP, 3/6/98]

Note: However, studies clearly indicate that most Dutch doctors do not comply with their own established practice guidelines. Recent Dutch research has found that (1) the majority of euthanasia deaths are involuntary (without the patients’ consent—a violation under Dutch guidelines) [ Remmelink Report, 1991], (2) that 55% of Dutch doctors interviewed in 1995 said either that they had killed patients without the patients’ consent or could foresee of a case where they would [New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), 11/28/96:1701], and (3) that the majority of Dutch physicians (59%) did not comply with the guideline requirement to report euthanasia and PAS deaths to the authorities. [NEJM, 11/28/96:1706] (See also, Update, 3-5/97:12.)

Offering death to Oregon’s poor as comfort care

Oregon’s State Health Services Commission has voted 10-1 to include PAS as a covered “medical service” for 270,000 low-income residents currently under the state’s Medicaid health care rationing plan. The commission added PAS to the “comfort care” treatment category for any “terminal illness, regardless of diagnosis.”

The Oregon Health Plan is unique among state Medicaid programs because it rations medical treatment for the poor by ranking services according to priority. Treatments ranked above a cut-off line are covered; those beneath the cut-off are not. The line is set every two years based upon community input, political clout, and budgetary constraints. In 1994, the list of possible treatments numbered 1-745, with the cutoff line at 606. Currently, only the top 578 of the 745 medical treatments are covered for the poor. PAS will rank 260th along with palliative care. [OR Dept. of Human Resources, Office of Med. Assistance Programs, Salem, OR, 3/98]

Dr. Gregory Hamilton, a Portland psychiatrist and head of Physicians for Compassionate Care, told the Health Services Commission, “Suicide is not comfort care.” “Comfort care results in a comfortable patient,” he explained. “Assisted suicide results in a corpse.” [Oregonian, 2/27/98] He also told the commission that, by funding PAS, the state would be pressuring vulnerable poor patients to choose suicide. “To offer state-funded suicide while failing to offer adequate care is unconscionable,” he said.

But some in Oregon see the inclusion of PAS as a treatment option for the poor as a matter of fairness. “The most discriminatory thing would be not to give this choice to the poor,” said commission member Ellen Lowe. “It should be included,” stated State Rep. George Eighmey (D-Portland). “It is part of the end-of-life care we give. It must be there to give people hope,” he added. According to DWDA co-author Barbara Coombs Lee, “Oregon voters created this health benefit.” “It would be discriminatory to say that dying Oregonians should have this choice, except for the poor,” she said.

“Yes, Oregonians voted on this, but nowhere… did Oregonians vote on paying for it,” argued Ellie Jenny, a consumer advocate and representative of Not Dead Yet. “There was never any mention in any of the election rhetoric that this would be funded by taxpayer money,” she added. [AP, 2/26/98] But, according to Hersh Crawford, head of Oregon’s Office of Medical Assistance Program, even if a lot of low-income patients opted for PAS, it wouldn’t cost that much. “These are cheap prescriptions,” he said, “and health care provider time will not be significant.” [AP, 2/27/98]

More PAS Guidebook Quotes

On conflicting rights:

“Sometimes rights of patients and providers are in direct conflict with each other under the Act. The patient’s right to privacy may conflict with the rights of health care providers to make informed personal decisions.” [p. 7]

On family needs and concerns:

“There are reports from the U.S. of family survivors who were informed, supportive, and present at the time of death, but who felt compelled to take action to complete the suicide after the medications induced sleep but not death. These survivors describe nightmares and guilt complicating their grief.” [p. 18]

On depression:

“Depression is a common diagnosis among terminally-ill patients desiring hastened death or physician-assisted suicide. Depression may impair patients’ ability to understand their options, diminish the ability to appreciate the benefits of life, and magnify the burdens. The presence of depression does not necessarily mean that the patient is incompetent..” [p. 31]

On doctors’ difficulty in recognizing depression:

“Studies indicate that many primary care physician have difficulty identifying significant depression and other mental health conditions. Given this diagnostic uncertainty and the gravity of the decision regarding physician-assisted suicide, it is strongly encouraged that the attending physician seek consultation from a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist in all cases.” [p. 22]

On financial incentives to end life:

Recent changes in health care reimbursement practices have increased public concerns about financial incentives that may influence patient care decisions…. Reimbursement methods can create actual or perceived conflicts for those caring for terminally-ill patients with expensive resource-intensive conditions. Patients and their families may fear that the quality of their care will be limited by the provider’s financial considerations.” [p. 42]

On emergency protocol:

“While emergency physicians do not qualify as attending physicians to prescribe medication to end life, they may care for patients who are brought to the ED [emergency dept.] by anxious family members or for patients who change their minds after self-administering the medication under the provisions of the Act…. The Act contains no guidance for providing information to other health care providers, such as emergency personnel, about the wishes and plans of patients.” [p. 38]

Ruling in Lee v. Oregon delayed

The constitutional challenge to the DWDA, Lee v. Oregon, may be revived. After the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed the case last year, ruling that the remaining plaintiff (a woman with muscular dystrophy) failed to show that the DWDA posed an immediate threat to her, U.S. District Judge Michael Hogan, the reversed trial judge who had ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, held another hearing to consider new claims in the case. Plaintiff attorney James Bopp argued that the 9th Circuit failed to consider that his client suffered a “stigmatic injury” under the DWDA. He also requested the addition of a new plaintiff in the case, a 57-year-old terminally-ill Corvallis man with lung cancer. Judge Hogan put off his ruling on the new arguments until April. [Oregonian, 2/18/98]

Final word on DEA ruling pending

So far there has been no final word from U.S. Atty. Gen. Janet Reno on whether the DWDA violates federal law. DEA Administer T. Constantine had issued a statement that the PAS law violated the Controlled Substance Act and that the DEA could revoke doctors’ prescribing licenses if they complied with the DWDA. Reportedly, a Justice Dept. team has concluded that the DEA cannot punish doctors, but Reno is waiting for more input. [AP, 1/23/98. See also, Update, 11-12/97:4.]

Not Dead Yet protests Hemlock Society’s euthanasia policy

Members of the disability rights group Not Dead Yet packed the Hemlock Society’s national headquarters in Denver, CO, on 1/23/98 to peacefully protest a Hemlock press statement proposing the creation of a special legal category for “mercy killing” cases, with no or very lenient penalties. The press release also called for a “judicial determination” when “it is necessary” to kill a family member who is mentally incompetent and whose life is deemed “too burdensome.”

The 12/3/97 press statement, issued by Hemlock Executive Director Faye Girsh, used a recent Louisiana murder case to justify Hemlock’s call for “merciful alternatives for those who act out of love.” The case involved David Rodriguez, 60, who was sentenced to life in prison for fatally shooting his 90-year-old father. Rodriguez told authorities that his father had severe arthritis and Alzheimer’s disease, and had repeatedly asked to be killed. He said that he shot his father out of sympathy.

According to Hemlock’s press release, Rodriguez had been unfairly treated by the legal system. “We suggest that, if these cases are to be prosecuted, they should be treated as special crimes of compassion and evaluated separately.” These cases, Hemlock held, are not malicious crimes, but cases where the “motivation is kindness and relief of suffering.”

The press statement did not stop there. Rather it went on to call for the legal acceptance of involuntary euthanasia for those individuals considered “burden- some,” “demented,” or “severely disabled”:

“Some provision should be made for a situation in which life is not being sustained by artificial means but, in the belief of the patient or his agent, is too burdensome to continue….

“A judicial determination should be made when it is necessary to hasten the death of an individual whether it be a demented parent, a suffering, severely disabled spouse or a child. Consultants should evaluate what other ways might be used to alleviate the suffering and, if none are available or are unsuccessful, a non-violent, gentle means should be available to end the person’s life.” [Hemlock Society USA, Press Release: “Mercy Killing: A Position Statement Regarding David Rodriguez,” PRNewswire, 12/3/97; emphasis added]

“The message is, ‘You’re not worth keeping alive,’” explained Luis Roman, a Not Dead Yet protester from East Chicago. “Someone else could decide my life has no value, my disability is too significant, too expensive,” said Deborah Cunningham, a wheelchair user from Memphis. Both Roman, who is blind, and Cunningham, along with eight other disabled protesters, were arrested and charged with trespassing and disturbing the peace. No one was jailed. Around 25 Not Dead Yet members had entered Hemlock’s 1,500 square-foot office, handcuffing themselves to desks and to each other.

Girsh told reporters that the press statement in question was her own and that she was not speaking on behalf of the Hemlock Society. But Diane Coleman, a founder of Not Dead Yet, said the statement indicates Hemlock’s real goal. “They’ve been lying to the public all along,” Coleman explained. “They have a very broad agenda that allows for involuntary euthanasia.”

But, according to Girsh, Not Dead Yet members misunderstand her position. The Hemlock Society is advocating legal leniency in the “mercy killings” of disabled individuals only when they are terminally ill, she said.

“She’s saying, ‘If you’re a burden, we want to put you out of our misery,” said Gayle Hafner, a disabled protester from Baltimore. “We can’t live with that kind of agenda,” she added. “I feel very threatened by this agenda.” [Denver Post, 1/24/98; Rocky Mountain News, 1/24/98]

But Hemlock USA is not the only right-to-die group to broaden the scope of its euthanasia agenda. In a fundraising letter last December, Compassion in Dying of Washington, the flagship chapter of the newly formed Compassion in Dying Federation, announced, “We have expanded our mission to include not only terminally ill individuals, but also persons with incurable illnesses which will eventually lead to a terminal diagnosis.” [CID of WA, Fundraising Letter, Dec. 1997; emphasis added.]

Commentary

Killing the Dying Is Not Palliative Care

by Eric M. Chevlen, M.D.

We are well beyond 1984. But it seems that the equating of opposites that George Orwell predicted for that year is still with us. No, Big Brother is not telling us that war is peace, or that ignorance is strength. This lie is bigger than that. The euthanasia lobby is telling us that killing is palliative care. This lie is such a whopper that even Orwell could not have dreamed of it.

Before this, the last big lie the euthanasia lobby tried to pull off was that the constitution had hidden within it—strange that no one ever noticed it before—the guarantee of a right to be killed. It was a strange sort of right, to be sure. The euthanasiasts could never make up their minds whether the right was restricted only to the dying, extended to the disabled, or was available for really anyone at all. They weren’t sure whether it could be exercised only by its “beneficiary,” or if any relative, including heirs to the estate, could declare that it was time to throw momma off the train.

In the end, it didn’t matter how the euthanasiasts tried to slice it. The Supreme Court was unanimous in calling it bologna. The constitution, the court found, guarantees our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but not to death, abandonment, and a dose of hemlock.

It wasn’t a bright day for the euthanasia lobby. But trying to make the best of the resounding judgment against them, the euthanasiasts clutched to their cold bosoms a fine point in the legal decision that has been inadequately noted in the press. The Court unanimously ruled out any constitutional right to euthanasia only because all parties in the case agreed that there is no legal impediment to palliative care. If there were such a legal impediment, then several of the Court members would certainly, and others would possibly, reverse their decision. This is not exactly the same thing as a constitutional right to palliative care, but it comes darn close.

Well, what would be wrong with that? Palliative care is nothing but the compassionate relief of pain and other symptoms in patients whose underlying illness is beyond effective medical treatment. It is the ideal that has driven medical, nursing, and hospice care from the time of Hippocrates to the present day. And during those twenty-five centuries of compassion, no one has been brazen enough to argue that palliative care includes “therapy” whose express purpose and inevitable result is the death of the patient.

Until now.

Last fall the state of Oregon enacted a law allowing physicians to prescribe lethal doses of medication to assist in a patient’s suicide. The state Health Services Commission, the governing body that rations Medicaid-funded care in Oregon, recently ruled that it would pay for this final prescription. One commission member, Amy Klare, said of physician-assisted suicide, “I don’t view this as producing death. These people are dying. It seems logical this would fall under comfort care.”

The euthanasia lobby remains perversely committed to the notion that the answer to suffering is killing the sufferer. There are many, they argue, whose pain is fundamentally untreatable, and whose lives are useless to themselves and worthless to society. If suffering cannot be treated, they persist, then killing the patient is the only way to eliminate the suffering. That means that killing the dying is palliative care, right?

Wrong. While some mistakes may be innocent, and some innocents may be mistaken, this bit of sophistry is brazen perversity, not compassionate of the dying, but contemptuous of their lives.

As a hospice medical director and board-certified specialist in pain medicine, I know the reality behind the distortions of the euthanasia lobby. My experience is consonant with that of numerous government-appointed blue ribbon panels. They, like I, have found that 90% of cancer patients in pain can have dramatic relief with relatively simple oral therapies. Virtually all of the rest of them can achieve relief with more sophisticated therapies.

Innumerable published medical studies have confirmed what I have witnessed in my own practice, that a request for assisted suicide is almost always an expression of clinical depression. Depression in the face of advanced illness is as treatable as it is in those who are otherwise healthy. The treatment might include medicine, counseling, or prayer, but it surely does not include a lethal injection.

Much mischief is made by the euthanasiasts of the alleged respiratory suppression effect of morphine. Like so much else they promulgate, this is a gross distortion. Experienced clinicians understand that there is an enormous difference between the effect of morphine during its first days of use as compared with its effect in the chronic setting. During the first few days of use, morphine may cause sedation; if used recklessly it may even cause respiratory suppression. But the respiratory system quickly acclimates to morphine therapy. With continued use, morphine—even in high doses—relieves pain, but does not make the patient stop breathing.

Euthanasiasts would like to argue that morphine therapy of the dying is a subterfuge for killing them. Perhaps they feel that such an argument might snatch for them the moral standing to argue that they merely want to do frankly what they allege others do secretly. But proper use of morphine in the final stage of life does not shorten life. In fact, good pain control probably prolongs life; without question, good pain control improves the quality of life.

Their final thrust against ethical care of the dying depends on a distortion of the principle of double effect. That well-accepted principle of medical ethics states that it is ethical to perform a medical intervention, even if it carries the risk of hastening death, if the intervention is designed to relieve severe suffering. They argue that their favorite therapy—lethal injection—is simply an extreme measure of pain relief, and that the death which accompanies the pain relief must be accepted on the principle of double effect. The vital point they gloss over, of course, is that the principle of double effect only applies when the undesired outcome is possible but not inevitable. Lethal injections are not simply possibly dangerous. They are purposely and inevitably so. To argue that a lethal injection is meant to relieve suffering, and the death of the patient is merely incidental, is like arguing that a swordsman merely intended to cut off his victim’s head, but did not mean to kill him.

First the euthanasiasts argued that there is a constitutional right to be killed. Now they argue that lethal injection is merely a variant of palliative care. Neither argument passes muster. The case for legalized euthanasia cannot be made on clinical grounds, any more than it can be made on legal or ethical grounds. It is not the lives of the dying that are worthless. It is the arguments of euthanasiasts that are worthless.

Words should not be deprived of their meanings any more than the dying should be deprived of the loving care that they deserve. War is not peace. And killing is not palliative care.

Eric M. Chevlen, M.D., is a cancer specialist and the director of Palliative Care at St. Elizabeth Health Center in Youngstown, Ohio. He also serves as a medical consultant to the IAETF. Copyright © 1998 by Eric M. Chevlen, M.D.

Michigan: Battlelines forming over assisted-suicide issue

The debate over assisted suicide is heating up in Michigan. At the center, of course, is an emboldened Jack Kevorkian, who is making more than a few people nervous with his body count now in the triple digits. But Kevorkian isn’t the only player in Michigan’s assisted-suicide controversy. The state legislature, governor, county prosecutors, and a group called Merian’s Friends are all lining up against Dr. Death—but for varied reasons.

Merian’s Friends wants PAS on ballot and Kevorkian out of the picture

Merian’s Friends—named for Merian Frederick, a 72-year-old Ann Arbor woman, who died in 1993 with Kevorkian’s assistance—is currently attempting to gather enough voter signatures to place its measure to legalize physician-assisted suicide on the November ballot.

The petition drive has been difficult for the group. With their volunteer signature gatherers falling way short of the needed 250,000 valid signatures and no money to pay for professionals, the group developed “Mortgages for Merian,” a program whereby supporters could loan the group thousands of dollars through pledges. In just three weeks, Merian’s Friends raised $130,000 in loans, allowing the group to hire National Voter Outreach, a professional signature gathering firm in Nevada. [Merian’s Friends, Press Release, 2/12/98] Yet, by mid-March, the group still only had about one-third of the signatures needed by 5/27/98 to qualify the measure.

One reason the petition drive may be faltering is that public support for assisted suicide in Michigan is dropping. According to Lansing, MI, pollster Ed Sarpolus, “Our tracking over the last several years shows support has waned from the mid-60s down to the mid-50s as the media has reported Jack Kevorkian has aided in suicides of people who aren’t terminally ill, suffering from chronic pain, or near death.” [Detroit News, 3/13/98]

Clearly, Merian’s Friends is doing everything it can to distance itself and the petition drive from the image of Dr. Death. “Merian’s Friends is not connected to Jack Kevorkian in any way,” the group’s chairman, Dr. Edward Pierce, told reporters. [Detroit News, 3/8/98] And Merian’s Friends’ Internet web page explicitly states, “Dr. Kevorkian: We are not associated with him and differ from his position in that our proposed law covers terminally-ill patients onlyand provides legal safeguards for them.” Even Wayne County prosecutor John O’Hair, a PAS supporter and Merian’s Friends board member, went public and wrote a letter to the Detroit News denouncing Kevorkian for assisting in the deaths of non-terminally ill people and for doing it in secrecy. “If Kevorkian is so convinced of the rightness of his actions,” wrote O’Hair, “he should describe openly what he does, and let the community judge on a case-by-case basis whether the law has been broken.” [O’Hair, Letters, Detroit News, 3/6/98]

Kevorkian scorns timid prosecutors

Kevorkian, not known for his ability to remain calm or reasoned in the face of criticism, responded to O’Hair’s letter with a scathing one of his own. Resorting once again to name-calling, Kevorkian accused O’Hair of being a “social criminal” and denounced him as a “liar and a cheat.” “Like the horde of other corrupt officials, you are putrefying the judicial system and helping to perpetuate a fraudulent dictatorship on a helpless populace,” he wrote.

In the letter, Kevorkian revealed just how much he disdains prosecutors who appease him or are timid about taking legal action to stop him. Referring to the 4/9/97 death of Heidi Aseltine, 27, in O’Hair’s county, Kevorkian wrote, “After the Heidi Aseltine case you dwelt on, I was emboldened to assert frankly my responsibility in subsequent cases because you were afraid to take action.” [Kevorkian, Letter, Detroit News, 3/10/98; emphasis added]

But O’Hair isn’t the only Metro area prosecutor for whom Kevorkian has shown no respect. Macomb County’s Carl Marlinga and Oakland County’s Dave Gorcyca are also on his list of timid prosecutors, with their counties being favorite dumping sites for Kevorkian-generated corpses.

Last year, when Marlinga backed out of an agreement with Kevorkian that would have permitted Kevorkian and others to drop off future bodies at a funeral home or the medical examiner’s office without fear of prosecution, Kevorkian retaliated by claiming another life in Marlinga’s jurisdiction. Marlinga, who, like O’Hair, is on the board of Merian’s Friends, was shocked by the death. “He [Kevorkian] told me there would be no more assisted suicides in Macomb County,” the prosecutor told reporters. “I question why he would make that representation and not follow through. I hate to think he would perform an assisted suicide in retaliation.…” Marlinga added. (See Update, 8-10/97:9.)

Gorcyca, who replaced Kevorkian foe Richard Thompson as Oakland County’s prosecutor, ran his election campaign on the promise not to waste taxpayers’ money by prosecuting Kevorkian. Shortly after taking office in January 1997, Gorcyca made good on that promise by dismissing all pending charges (19 felony counts) against Kevorkian as well as other charges against members of his death team. Gorcyca made it clear that any future prosecutions of Kevorkian in Oakland County would be unlikely until the Michigan legislature passed “a clearly enforceable law controlling assisted suicide.” (See Update, 1-2/97:8.)

The fact that Gorcyca essentially gave the death team a free-hand in Oakland County has not protected him against Kevorkian’s tirades. After authorities confiscated items used in the recent assisted death of a 21-year-old student (see p. 10), Kevor- kian stood in front of the Oakland County courthouse with a sign reading, “I did it. Why doesn’t the corrupt prosecutor arrest me?” Kevorkian also warned, “I can’t talk about it yet, but I’ve got something planned that will curl Gorcyca’s hair.” [Detroit Free Press, 3/3/98]

Kevorkian’s master plan

There has been much speculation about what Kevorkian plans to do to “curl Gorcyca’s hair.” Many thought that Kevorkian was planning something special on the occasion of his 100th assisted death, which occurred on 3/13/98 with the demise of Michigan resident Waldo Herman, 66. But, Herman’s death occurred in Wayne County without much fanfare, out of Gorcyca’s jurisdiction. Others speculate that Kevorkian is saving his first organ-harvesting assisted suicide for Gorcyca and other targeted Oakland County officials.

One thing is for sure, Kevorkian is inching closer to fulfilling his master plan for the practice of what he calls “obitiatry,” which includes the harvesting of organs from and the experimentation on human subjects. The plan is outlined in his 1991 book, Prescription: Medicide, and detailed in his 1992 article, “A Fail-Safe Model for Justifiable Medically-Assisted Suicide,” published in the American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry.

Kevorkian has already announced his plans to remove organs from willing assisted-suicide “clients” and offer the organs for transplantation on a “first-come, first-served” basis. In fact, Kevorkian attorney Geoffrey Fieger told reporters last October that a liver and a kidney would be made available at a press conference within a month. To date that has not happened, but if Kevorkian has his way, eventually it will. “We’ve achieved Phase 1, which is helping people end their suffering,” Kevorkian has said. “The second phase is getting some benefit back to save other people’s lives.” [AP, 10/23/97]

The sorcerer’s apprentice

Part of Kevorkian’s plan is to establish “obitiatry” as a medical specialty. Toward that end, he has expanded his death service to include psychiatrist Georges Reding as his “apprentice.” Reding, 72, surfaced as a Kevorkian team member in 1996, reportedly using his psychiatric skills to examine and evaluate prospective assisted-suicide “clients” and their mental competence. Referring to those “clients,” Reding once told New York Times reporter Jack Lessenberry, “They have all been more sane than I am.” [NY Times, 8/11/96]

But Reding’s professional career, like Kevorkian’s, has been controversial. He is particularly known for his theory that most mental patients should not be hospitalized or on drugs. According to Bev Lewis, past president of the patient advocacy group Alliance for the Mentally Ill, “Reding believed no one is ever in need of hospitalization and often told patients to stop taking medication, such as lithium, with disastrous results.” She also said that Reding “never stays anywhere for long because there isn’t any place he’s been that will put up with his behavior.”

Prior to his moving to Michigan in 1990, Reding held several positions in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. From 1990 to 1996, Reding had at least four different jobs in Michigan. He worked for a year at the Kalamazoo Community Mental Health group, where 15 mental health patients and advocates complained in writing about him to state health officials. They alleged that Reding’s unorthodox methods had caused patients to suffer both mentally and physically. Records show that six formal complaints in five years were filed with the state claiming rough treatment of patients as well as his use of unorthodox methods. None of the complaints resulted in disciplinary action. [UPI, 7/31/96; Detroit Free Press, 12/5/97]

Now Reding is completing a “fellowship” under Kevorkian, meaning that he is taking a more active part in the deaths. In fact, he conducted his first assisted suicide on Martha Wichorek on 12/3/97. He also played a major role in the 1/19/98 death of Carrie Hunter, 35, a transsexual with AIDS. UPI, 1/19/98; Reuters, 1/19/98; LA Times, 1/19/98; Detroit News, 1/20/98]

Having both Kevorkian and Reding adding to the casualty list, is alarming—one “obitiatrist” and another “in training” (both with checkered pasts) specializing in death, organ harvesting, and human experimentation.

Death on demand

Many of the recent deaths are proof positive that the name of Kevorkian’s game is death on demand. The overwhelming majority of victims have not been terminally ill. In the case of 82-year-old Martha Wichorek, her only maladies were readily treatable and normal for someone her age. Reportedly, she just wanted to die. [Detroit Free Press, 12/5/97; UPI, 12/4/97]

Another controversial death was that of Franz-Johann Long, 53. According to Fieger, Long was dying and in severe pain from bladder cancer. Fieger also said that Long had been given a thorough psychiatric examination by Reding, who found him to be fully competent. But Long’s sister told Oakland County authorities that her brother had been declared incompetent in 1986 and that, since that time, she has served as his legal guardian. Other family members verified that Long had been under psychiatric care since the age of three. Not surprisingly, the autopsy revealed that he was not dying. According to Oakland Co. Medical Examiner Dr. L.J. Dragovic, “Even if he had the cancer, it was very superficial. It would have been in the very early stages on his bladder and surgically curable without a doubt.” [Oakland Press, 12/31/97:A6]

But it was Roosevelt Dawson’s death on 2/26/98 which caused the most controversy. Dawson, who was 21 at the time of his death, had been a student at Oakland University when he contracted a virus which left him paralyzed from the neck down. He was not terminally ill nor was he in physical pain. He said he wanted to die because he could no longer live life as he used to. Just hours after being released from a Grand Rapids hospital where he had been treated for five months, and after talking with Kevorkian only a few times by phone, Dawson died in his mother’s Southfield apartment with Kevorkian, Reding, and Neal Nicol, a longtime Kevorkian aide, present. According to a Hospice of Michigan physician, Dr. Walter Hunter, “The evaluation process to find out why an individual is requesting death takes a lot longer than a car ride from Grand Rapids to Southfield.” But Fieger dismissed all critics, saying the issue has always been quality of life. Never mind that Kevorkian didn’t lay eyes on Dawson until the night he died. [Detroit News, 3/1/98, 3/3/98; Detroit Free Press, 2/27/98, 3/3/98]

Michigan Legislature passes ban

In response to Kevorkian and the bogus claim that there is no anti-assisted suicide law in Michigan, the state House of Representatives passed a bill explicitly making assisted suicide a five-year felony. The Senate already passed the bill last December, but, since the House version was amended slightly, the measure will go back to the Senate for its expected approval. Gov. John Engler has indicated he will sign the bill into law. Because the bill did not get the two-thirds vote required to allow the ban to take effect immediately, it is scheduled to be enacted in April 1999. However, there are on-going efforts in the works to make the ban immediate. In addition to passing the ban, the House dealt right-to-diers a second significant blow by killing a bill which would have placed a Merian’s Friends-type referendum on the November ballot. [Detroit Free Press, 3/13/98]

Meanwhile, Macomb and Wayne Co. prosecutors have indicated that they might not wait a year for the new ban to take effect before charging Kevorkian. Marlinga said he has a 10/13/97 voice recording of Kevorkian anonymously telling police the location of Annette Blackman’s body. Wayne Co. Deputy Chief Prosecutor Douglas Baker said that he also would prosecute under common law, given enough evidence. Gorcyca, however, remains hesitant. [Detroit News, 3/16/98]

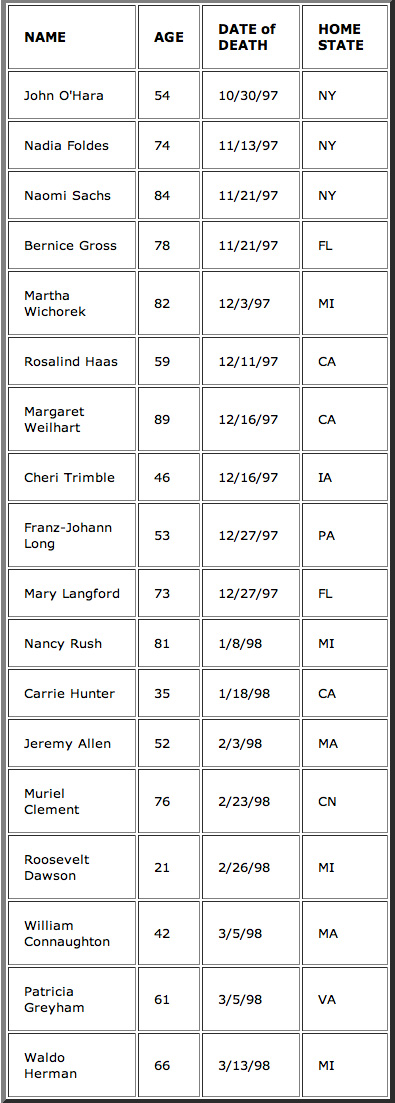

Reported KEVORKIAN VICTIMS since last Update

News Notes

Canadian physician Maurice Genereux has been stripped of his license to practice medicine. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario revoked his license after he pleaded guilty to professional misconduct. He was also charged with “engaging in a disgraceful or dishonorable act” and with “improper prescription of drugs.” [AP, 3/12/98]

According to Dr. Dody Bienenstock, head of the committee that regulates Ontario’s physicians, “The college finds Dr. Genereux’s behavior reprehensible and serious; an unacceptable breach of standards and obligations.” [CP, 3/12/98; Toronto Sun, 3/13/98]

Last December, Genereux, 51, became the first doctor in Canada to be convicted of the crime of assisted suicide. A Toronto specialist working with patients with HIV and AIDS, Genereux prescribed lethal doses of barbiturates to two of his HIV patients. Both took the lethal prescription. One died as friends watched; the other lived after a friend found him and got help. Genereux is due to be sentenced for the criminal charges on April 29. (See Update, 11-12/97:9.)

Another Canadian physician Nancy Morrison, who had been charged with first-degree murder in the 11/10/97 death of a cancer patient, has been freed by the court. Nova Scotia Provincial Judge Hughes Randall threw out the case against the Halifax doctor, saying that the prosecution failed to make its case. According to reports, Morrison, an intensive care doctor, had given Paul Mills an injection of potassium chloride which proved fatal. Mills allegedly was within hours of dying and was in great discomfort. Morrison told reporters that the judge’s dismissal of the case was “a step along the way.” “It’s not over yet,” she added. [UPI, 2/27/98; CP, 2/27/98]

*****

Dr. Eugene Turner, a Washington State pediatrician in rural Port Angeles, has been accused by the state Medical Quality Assurance Commission of unprofessional conduct in the death of 3-day old Conor Shamus McInnerney on 1/12/98. Turner has admitted that he placed his hand over the baby’s mouth and nose, which resulted in the baby’s death. Commission director Bonnie King said, “The commissioners felt that the act of terminating the child’s life was unprofessional conduct.” Turner has been banned from making decisions on when to end patient resuscitation, pending an investigation by the commission.

The baby had stopped breathing while nursing and was rushed to Olympic Memorial Hospital’s emergency room. He was without a detectable pulse for 39 minutes before doctors managed to get his heart beating. His prognosis was considered “dismal,” and his parents agreed to stop life support. They went home thinking that their baby had died.

Later, a nurse noticed that the baby was gasping and turning pink in color. But after 2 more hours of treatment, Turner declared the baby brain-dead. He never did inform the parents that the baby had started breathing on his own. He said he didn’t want them to have to go through the baby “dying” twice. A nurse subsequently informed hospital officials that she and a fellow nurse had seen Turner block the baby’s airways with his hand. The incident is reportedly under a police investigation. [AP, 2/12/98, 2/23/98, 2/24/98]

*****

Charles Edward Hall, the AIDS patient who unsuccessfully challenged Florida’s law banning assisted suicide all the way to the state’s Supreme Court, died on 3/9/98. His death came naturally, during his sleep, at home, surrounded by family members.

Hall was the only surviving patient/plaintiff when the assisted-suicide case, Krischer v. McIver, was heard by the Florida Supreme Court. The high court ended up overturning Circuit Judge S. Joseph Davis, who had ruled in Hall’s favor by granting physician Cecil McIver the right to help end Hall’s life at a time and in the manner of Hall’s choosing. McIver and Hall did not have a doctor/patient relationship prior to lawsuit or after. When asked about Hall’s death, McIver matter-of-factly told reporters that he had not been in contact with Hall for some time, but he knew that Hall was sick, bedridden, and in pain. “He lived longer that anticipated,” McIver added. [Tampa Tribune, 3/10/98, Miami Herald, 3/11/98]

*****

New Yorker John Bement, 57, was found guilty of second-degree manslaughter for his involvement in his wife’s death. He will be sentenced on May 4, and could face up to 15 years in prison. His wife, Judith, had ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). She also had a copy of Final Exit, a how-to-commit-suicide manual. Bement followed the manual’s directions, mixing prescription barbiturates and pain-killers with pudding and vodka, which he spoon-fed to his wife of 33 years. Then, he says, he placed a plastic bag over her head before she was completely out. He and one of his wife’s daughters, Cynthia Hull, say that it was Judith who wanted to die. “The disease had consumed her,” Hull said. “She couldn’t fight it any longer. She was tired of fighting it. In her mind, she had done everything she could.”

But Judith’s other daughter adamantly disagrees. According to Susan Randall, “My Mom did not want to die that night.” Randall says that her mother was having a good day. She did not say good-bye to her daughter earlier in the day when Randall came to visit, nor did she leave any note. “Closure was a real big thing for her,” Randall explained. “My mom would not have left this earth without closure.”

It was Randall who helped police get the evidence they needed for Bement’s conviction. She secretly taped her conversations with her step-father and her sister, who helped mix the poisonous pudding while Bement went to the store to get the vodka. Hull, however, was not indicted by the grand jury. She had been present when Judith ingested the deadly concoction, but left to go pick up her 11-year-old daughter at a friend’s house while her mother was still conscious. [AP, 2/20/98, 2/21/98, 3/8/98]